With tens of millions of Americans out of work and unable to pay their bills amid the COVID-19 pandemic, two Democratic lawmakers are urging the credit reporting bureaus to do more.

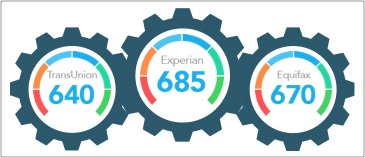

In a letter to Equifax, Experian and TransUnion — the three credit reporting bureaus that collect information on consumers’ credit — Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Sen. Brian Schatz of Hawaii said they want to know what the three bureaus are doing to protect the credit scores of Americans beyond what was set forth in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act.

The historic relief bill put special protections in place to prevent creditors from reporting missed payments, as long as the consumer entered into a payment modification agreement. The account has to have been in good standing before the crisis to be eligible.

The senators argue those amendments to the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) don’t go far enough and don’t protect consumers’ credit scores from missed payments on auto loans, credit cards, payday loans and other types of debts.

“If American families and consumers are piled under a mountain of debt during this pandemic and once it ends, the country will struggle to emerge from a deep recession,” Warren and Schatz wrote in the letter. “This means that when the crisis is over, months of late or missed payments could add up to not just a mountain of debt, but a cratering credit score that takes away the shovel they might use to dig themselves out.”

Payment history accounts for around 40% of a consumer’s credit score, and if the pandemic causes scores to decline due to missed payments, it could mean the cost of borrowing rises. It could also preclude someone from getting a personal loan, purchasing a new car, securing a mortgage or rental, getting insurance, and landing certain jobs. That, in turn, could slow the recovery.

“Our economic revival depends on millions of Americans’ ability to resume their lives after the pandemic abates and the economy reopens. Permanently marred credit scores pose a risk to individuals and to our collective recovery,” the senators wrote.

Credit Reporting Bureaus Think CARES Act Goes Far Enough

The push on the part of the two lawmakers is being met with resistance from the credit reporting bureaus, who argue the CARES Act is the proper response to the crisis because it requires borrowers to reach out to their lenders and work something out.

“Suppression is intended to help those people who are having a difficult time during the COVID-19 crisis because of a loss of income,” said Francis Creighton, president and CEO of the Consumer Data Industry Association, the industry’s trade group. “However, the systematic suppression or deletion of information that undoubtedly predicts a greater likelihood of delinquency or default will cause creditors to make significant changes in how they use credit information to make loans.”

Creighton argues that if the senators’ suggestion became law, lenders would be more choosy in who they issue loans to. That would mean fewer people would be approved and the cost of borrowing would be more expensive.

“Lenders are already tightening credit across the economy. Suppressing negative information will force them to become even more risk-averse, further cutting back credit and resulting in higher prices for those who do get loans. Suppression is a far worse threat to people getting affordable credit,” Creighton said.

That’s not to say the industry isn’t trying to help struggling consumers during the pandemic. All Americans will have access to free weekly credit reports from all three credit reporting agencies for a year. However, the credit reports don’t include credit scores, which may be obtained for fee.

Consumers Need All the Help They Can Get

Despite the opposition on the part of the credit reporting industry’s association, consumer debt advocates say Warren and Schatz’s idea makes sense if it helps consumers come back from the crisis, which will undoubtedly eclipse the Great Recession of a little more than a decade ago. The longer social distancing lasts and the economy remains shuttered, the worse off consumers’ credit scores may be. For some, it won’t only make it more expensive to borrow money but it could hurt their chances of clawing out from the economic ruin brought on by the pandemic.

“It’s not as simple as everyone gets back to work,” said Martin Lynch, the compliance manager and director of education at Cambridge Credit Counseling. “A lot of the businesses are closed permanently and a lot of people are looking for a new line of work. Having a credit score stand between them and that next job is going to be yet another obstacle.”