Chronic saving and a preference for cash leads to unintended consequences: the unconventional path to a comfortable life.

In rural Maryland, after quitting time the bars are almost always filled with workers discussing sports, spouses and kids, the price of gas and low wages. Growing up in an economically challenged region may have a long-lasting impact on the young, even after economic situations change for the better.

That’s exactly what happened to Ray Butler, a 63-year-old man who managed to live his life so frugally, it almost cost him.

A Cash Beginning

“We didn’t have much growing up. My mom worked three jobs and my dad took care of us,” muses Butler. “I learned the value of a dollar early. When I was 15, I went to work for my sister’s husband – and I’ve been saving ever since.”

We didn’t have much growing up. My mom worked three jobs and my dad took care of us

“It just wasn’t what you’d expect,” says Butler. “I never borrowed money. I always paid in cash. I had a savings account. I made good money. I didn’t spend much. But, when I wanted to take out a loan, I couldn’t get the best rates.”

Butler has been cautious with money all his life – possibly too cautious, as his frugal nature and desire to build substantial savings were no help when banks wanted to charge him the highest interest rates to buy a home and a small business.

Buying things with a debit card or cash will not build your credit score, according to Holly Petraeus and Corey Stone of the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau‘s Office of Servicemember Affairs. “[It] doesn’t establish a credit repayment history that will be reported to a credit-reporting company. So when you do need a loan for a big-ticket item like a car or home, you won’t have the credit file to make a lender willing to take a chance on you.”

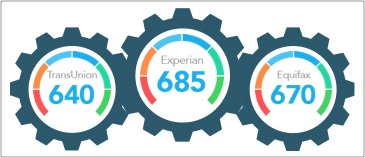

Butler’s experiences with credit are not common, but they serve as a word of caution to people who try to correct previous credit mishaps by overcompensating and avoiding credit use altogether. “Credit scores are partly based on experience over time,” say Petraeus and Stone. “The more evidence you have on how you get and pay for credit, the more information there is to determine whether you are a good credit risk.” The smart thing to do is to borrow manageable amounts of money and do so continually over several years, but it can be hard to change old habits.

Butler grew up poor and started saving money as soon as he started working at age 15. By the time he was 20, he had $28,000 in the bank, the equivalent of $155,000 in 2016 dollars. He ended up using half of it to purchase a garage and $4,000 as a down payment on a home for him and his fiancée Carol.

It was a busy few years. Butler started his own body shop business, and with his savings largely spoken for, he used a Sears card to help finance equipment purchases. Carol helped him run the business, but it never really took off. After a few years, Butler closed up shop and went to work in the collision center of a local car shop – a position he still holds today.

He married Carol in 1978. At the time, she would use the Sears card to buy tools for Butler’s birthday and the holidays, but the high interest rate made it difficult to pay off the card in full. One year they used an income tax refund to pay off the card, and, now blissfully free from debt other than a mortgage, they decided to start a family.

Modest Living and Modest Interest Rates

The Butler family lived within their means, and within a few years, Carol was able to quit working and stay at home to raise their daughter. Butler continued to grow their savings and rarely used credit.

In 1989, Butler decided it was time to add on to the house for his growing family. He planned to add a master bathroom and a large family room. Intending to do most of the work himself, he refinanced the remaining home mortgage to take out enough money to build the addition.

He got the loan easily enough, but once again couldn’t get the best rate. “I was surprised at the interest rate they gave me. I had been with the bank for years,” said Butler.

In fact, the interest rate was high for someone who owed no other debt than on his house. The problem was that his credit was largely untested. Despite years of saving and careful purchases, Butler’s credit rating was not as high as it could be.

Use It or Lose It

Although you don’t hear about it often, it is possible to use credit so infrequently that when it comes time to borrow money, some may find their credit score is too low to get the best interest rate. Finding himself with no other option, Butler ended up taking out a loan at a higher interest rate and making do.

After understanding the role credit scores play in determining access to loans, Butler embraced a “use it or lose it” philosophy to money management.

Rather than try to use credit cards to boost his credit rating, he kept his focus on assets. He paid his home loan down and refinanced a third time. This time, he got a better rate and enough money to renovate his garage and turn it into storage units that he could rent out. Once the units were done, they started earning money almost immediately. Rather than pay off the loan quickly with money from the units, Butler continued making his regular payments, reducing the amount he owed over time.

He found that the more he used his credit, the better the terms he was able to negotiate. Using this method, his credit rating rose to over 800 and stayed there. Now, at age 63, Butler is able to get the rates he wants, because while he always knew the value of a dollar, today he knows the value of credit.